The first commentary was written by the former editor of Indian Country Today, and was published on indianz.com.

The first commentary was written by the former editor of Indian Country Today, and was published on indianz.com.The second commentary was also published on indianz.com.

The third commentary was written by a Libertarian.

Tim Giago: Thanksgiving -- A holiday of the imagination

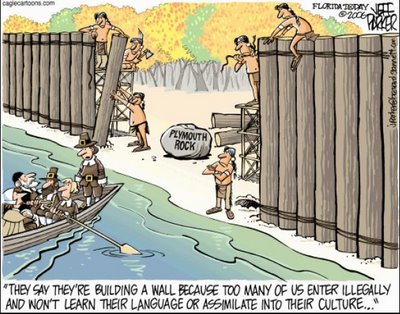

There is a saying amongst the Lakota that when the Pilgrims first landed at Plymouth Rock they fell on their knees and prayed and then they fell on the Indians and preyed.

So much fabrication has been woven into the landing of the Pilgrims and their dealings with the indigenous people they met that first year it is hard to separate fact from fiction.

The Mayflower actually landed on Cape Cod on November 11, 1620 at a place that would become Provincetown. The landing site proved to be unsuitable. Robert Coppin, the Mayflower’s pilot, remembered another site more suitable to permanent settlement.

On December 16, 1620 the settlers sailed into the harbor the Indians called Patuxet. There are no 17th Century sources that mention landing on a rock, but the Pilgrims called the landing site Plymouth Rock nonetheless.

We were all taught about the first winter in which many settlers died until only 52 of the original 102 remained alive. The history books also teach us that the Indians helped the settlers survive by teaching them how to plant corn, squash and other vegetables.

The Wampanoag were the first Indians to actually meet and speak with the Pilgrims. An Abenaki named Samoset who spoke English he learned from fisherman who visited the coast introduced them to a man named Tisquantum or Squanto. Squanto had been taken to England as a prisoner and spoke fairly fluent English.

Strangely enough, most early works of art depicting the first harvest feast of the Pilgrims shows the settlers fleeing from a hail of arrows.

The first modern image showing the Indians and settlers enjoying a feast in harmony did not occur until after the so-called Indian wars were settled. It was only after the Indians became the Vanishing Americans that they became an integral part of the Pilgrim story.

A stanza from the poem by Felicia Hemans (1793 – 1835) about the landing of the Pilgrims goes:

There is a saying amongst the Lakota that when the Pilgrims first landed at Plymouth Rock they fell on their knees and prayed and then they fell on the Indians and preyed.

So much fabrication has been woven into the landing of the Pilgrims and their dealings with the indigenous people they met that first year it is hard to separate fact from fiction.

The Mayflower actually landed on Cape Cod on November 11, 1620 at a place that would become Provincetown. The landing site proved to be unsuitable. Robert Coppin, the Mayflower’s pilot, remembered another site more suitable to permanent settlement.

On December 16, 1620 the settlers sailed into the harbor the Indians called Patuxet. There are no 17th Century sources that mention landing on a rock, but the Pilgrims called the landing site Plymouth Rock nonetheless.

We were all taught about the first winter in which many settlers died until only 52 of the original 102 remained alive. The history books also teach us that the Indians helped the settlers survive by teaching them how to plant corn, squash and other vegetables.

The Wampanoag were the first Indians to actually meet and speak with the Pilgrims. An Abenaki named Samoset who spoke English he learned from fisherman who visited the coast introduced them to a man named Tisquantum or Squanto. Squanto had been taken to England as a prisoner and spoke fairly fluent English.

Strangely enough, most early works of art depicting the first harvest feast of the Pilgrims shows the settlers fleeing from a hail of arrows.

The first modern image showing the Indians and settlers enjoying a feast in harmony did not occur until after the so-called Indian wars were settled. It was only after the Indians became the Vanishing Americans that they became an integral part of the Pilgrim story.

A stanza from the poem by Felicia Hemans (1793 – 1835) about the landing of the Pilgrims goes:

Ay, call it holy ground,

The soil where first they trod!

They have left unstain’d what where they found –Freedom to worship God.

Perhaps, a century later, an Indian poet would have written;

Hau, call it stolen ground,

The soil where first they trod!

They have left a stain over all they found,

And took our freedom to worship God.

The indigenous people of what was to become New England had little to be thankful for in the ensuing years. Many died of small pox, measles and other diseases to which they had no immunity or they died at the hands of the settlers. Their villages were burned to the ground and their women and children sold into slavery or murdered. Bounties were placed on those who survived and soon hunters and trappers showed up at the trading posts collecting money for their “redskins.”

George Washington chose a day to give thanks for the establishment of a “new nation” in 1789.

After the War of 1812 James Madison called for a day of thanks in 1815. History does not expound upon the fact that it was the combined Indian forces of Creek and other Southeastern tribes that helped turn the tide in favor of the Americans at the Battle of New Orleans, a battle that was essential in turning the war against the British.

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln, at the urging of Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, set aside the fourth Thursday of November as Thanksgiving Day. In 1941 Congress passed a joint resolution making the fourth Thursday of November the official holiday of Thanksgiving.

During the 1960s Indian activists began to gather at Plymouth Rock on Thanksgiving Day to protest the treatment of the indigenous people and to rail against a holiday based on fiction.

It is a general belief that the United States government began to visualize Indians as part of the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth Rock in order to demonstrate a move toward diversity. Immigrants from many nations, some not so fair and blonde, landed at Ellis Island in search of freedom and a new life.

By this time the Massacre at Wounded Knee had happened and some historians recorded it as the last great battle between the Indians and the government. Wounded Knee was listed as a battle between troops of the Seventh Cavalry and the Sioux. Keep in mind that it was just a short 13 years from the day Lincoln set a date for Thanksgiving to the Battle at the Little Big Horn in 1876. The troops of the Seventh Cavalry had celebrated Thanksgiving just five weeks before they slaughtered innocent men, women and children at Wounded Knee.

With the Indian wars far behind, and the Indian, now listed as “The Vanishing American,” it was now almost romantic to create a time of peace and tranquility when the Pilgrims brought the Indians to their table at Thanksgiving to share a sumptuous meal centered around the turkey.

And so it seems the American Indian had to be placed on the “Most Endangered Species” list before he could be seated at the table with the Pilgrims. And of course, the Indian by then had progressed from prey to pray.

http://www.indianz.com/News/2006/017037.asp

And so it seems the American Indian had to be placed on the “Most Endangered Species” list before he could be seated at the table with the Pilgrims. And of course, the Indian by then had progressed from prey to pray.

http://www.indianz.com/News/2006/017037.asp

Thanksgiving is a lie

by Tommi Avicolli Mecca

Thanksgiving is a lie. Just like Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny.There's no more truth to the Hallmark moment of Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing a feast of squash, corn and turkey than there is to Betsy Ross sewing the first American flag. No definitive historical evidence exists to prove either patriotic legend. According to my favorite history text, "Lies My Teacher Told Me" by James W. Loewen, it was all manufactured to create a feel-good beginning for this country.

Thanksgiving wasn't invented by the Pilgrims. By the time the Mayflower pulled up at Plymouth Rock in 1620, Native Americans in that part of the country already had a rich tradition of marking the fall harvest with a major fiesta.

The day wasn't recognized nationally until 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln declared it a holiday. He had an entirely different motive than honoring the Pilgrims: Morale during the bloody Civil War. America needed a warm fuzzy holiday to make it feel good about itself again.

The Pilgrims were latecomers to the legend, not getting added to the mix until the 1890s. Of course, some major revisions had to be done to make heroes of those guys. The truth is: When the Pilgrims arrived on the coast of Massachusetts, they found a deserted Native American settlement. Unburied human bodies were scattered everywhere. The survivors had vanished. The villagers had been wiped out by a plague, brought to the "new world" years before by the Europeans. The immune system of the native peoples had no defense against those diseases.

Many in Europe couldn't be happier. Good Christian that he was, King James of England called the death of millions of Native Americans "this wonderful plague." He thanked God for sending it. Other preachers of the day echoed this same sentiment. They believed that God had aided the conquest of the new land by sending disease to ravage the native populations, so that the English could have it. How convenient for them that God was on their side.

The Pilgrims, who were ill-equipped to survive in the harsh environment they found themselves in, immediately took advantage of the situation. They proceeded to rob food (including corn and squash) and pottery from the deserted Native village. They also stole from Indian graves. Within about 50 years of arriving, they had slaughtered most of the native population in the area that wasn't already killed by the plague.Not the touchy-feelie story you'll see on TV this week.

by Tommi Avicolli Mecca

Thanksgiving is a lie. Just like Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny.There's no more truth to the Hallmark moment of Pilgrims and Native Americans sharing a feast of squash, corn and turkey than there is to Betsy Ross sewing the first American flag. No definitive historical evidence exists to prove either patriotic legend. According to my favorite history text, "Lies My Teacher Told Me" by James W. Loewen, it was all manufactured to create a feel-good beginning for this country.

Thanksgiving wasn't invented by the Pilgrims. By the time the Mayflower pulled up at Plymouth Rock in 1620, Native Americans in that part of the country already had a rich tradition of marking the fall harvest with a major fiesta.

The day wasn't recognized nationally until 1863 when President Abraham Lincoln declared it a holiday. He had an entirely different motive than honoring the Pilgrims: Morale during the bloody Civil War. America needed a warm fuzzy holiday to make it feel good about itself again.

The Pilgrims were latecomers to the legend, not getting added to the mix until the 1890s. Of course, some major revisions had to be done to make heroes of those guys. The truth is: When the Pilgrims arrived on the coast of Massachusetts, they found a deserted Native American settlement. Unburied human bodies were scattered everywhere. The survivors had vanished. The villagers had been wiped out by a plague, brought to the "new world" years before by the Europeans. The immune system of the native peoples had no defense against those diseases.

Many in Europe couldn't be happier. Good Christian that he was, King James of England called the death of millions of Native Americans "this wonderful plague." He thanked God for sending it. Other preachers of the day echoed this same sentiment. They believed that God had aided the conquest of the new land by sending disease to ravage the native populations, so that the English could have it. How convenient for them that God was on their side.

The Pilgrims, who were ill-equipped to survive in the harsh environment they found themselves in, immediately took advantage of the situation. They proceeded to rob food (including corn and squash) and pottery from the deserted Native village. They also stole from Indian graves. Within about 50 years of arriving, they had slaughtered most of the native population in the area that wasn't already killed by the plague.Not the touchy-feelie story you'll see on TV this week.

The Great Thanksgiving Hoax

By Richard J. Maybury

Each year at this time school children all over America are taught the official Thanksgiving story, and newspapers, radio, TV, and magazines devote vast amounts of time and space to it. It is all very colorful and fascinating.

It is also very deceiving. This official story is nothing like what really happened. It is a fairy tale, a whitewashed and sanitized collection of half-truths which divert attention away from Thanksgiving's real meaning.

The official story has the pilgrims boarding the Mayflower, coming to America and establishing the Plymouth colony in the winter of 1620-21. This first winter is hard, and half the colonists die. But the survivors are hard working and tenacious, and they learn new farming techniques from the Indians. The harvest of 1621 is bountiful. The Pilgrims hold a celebration, and give thanks to God. They are grateful for the wonderful new abundant land He has given them.

The official story then has the Pilgrims living more or less happily ever after, each year repeating the first Thanksgiving. Other early colonies also have hard times at first, but they soon prosper and adopt the annual tradition of giving thanks for this prosperous new land called America.

The problem with this official story is that the harvest of 1621 was not bountiful, nor were the colonists hardworking or tenacious. 1621 was a famine year and many of the colonists were lazy thieves.

In his 'History of Plymouth Plantation,'the governor of the colony, William Bradford, reported that the colonists went hungry for years, because they refused to work in the fields. They preferred instead to steal food. He says the colony was riddled with "corruption," and with "confusion and discontent." The crops were small because "much was stolen both by night and day, before it became scarce eatable."

In the harvest feasts of 1621 and 1622, "all had their hungry bellies filled," but only briefly. The prevailing condition during those years was not the abundance the official story claims, it was famine and death. The first "Thanksgiving" was not so much a celebration as it was the last meal of condemned men.

But in subsequent years something changes. The harvest of 1623 was different. Suddenly, "instead of famine now God gave them plenty," Bradford wrote, "and the face of things was changed, to the rejoicing of the hearts of many, for which they blessed God." Thereafter, he wrote, "any general want or famine hath not been amongst them since to this day." In fact, in 1624, so much food was produced that the colonists were able to begin exporting corn.

What happened?

After the poor harvest of 1622, writes Bradford, "they began to think how they might raise as much corn as they could, and obtain a better crop." They began to question their form of economic organization.

This had required that "all profits & benefits that are got by trade, working, fishing, or any other means" were to be placed in the common stock of the colony, and that, "all such persons as are of this colony, are to have their meat, drink, apparel, and all provisions out of the common stock." A person was to put into the common stock all he could, and take out only what he needed.

This "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need" was an early form of socialism, and it is why the Pilgrims were starving. Bradford writes that "young men that are most able and fit for labor and service" complained about being forced to "spend their time and strength to work for other men's wives and children." Also, "the strong, or man of parts, had no more in division of victuals and clothes, than he that was weak." So the young and strong refused to work and the total amount of food produced was never adequate.

To rectify this situation, in 1623 Bradford abolished socialism. He gave each household a parcel of land and told them they could keep what they produced, or trade it away as they saw fit. In other words, he replaced socialism with a free market, and that was the end of famines.

Many early groups of colonists set up socialist states, all with the same terrible results. At Jamestown, established in 1607, out of every shipload of settlers that arrived, less than half would survive their first twelve months in America. Most of the work was being done by only one-fifth of the men, the other four-fifths choosing to be parasites. In the winter of 1609-10, called "The Starving Time," the population fell from five-hundred to sixty.

Then the Jamestown colony was converted to a free market, and the results were every bit as dramatic as those at Plymouth. In 1614, Colony Secretary Ralph Hamor wrote that after the switch there was "plenty of food, which every man by his own industry may easily and doth procure." He said that when the socialist system had prevailed, "we reaped not so much corn from the labors of thirty men as three men have done for themselves now."

Before these free markets were established, the colonists had nothing for which to be thankful. They were in the same situation as Ethiopians are today, and for the same reasons. But after free markets were established, the resulting abundance was so dramatic that the annual Thanksgiving celebrations became common throughout the colonies, and in 1863, Thanksgiving became a national holiday.

Thus the real reason for Thanksgiving, deleted from the official story, is: Socialism does not work; the one and only source of abundance is free markets, and we thank God we live in a country where we can have them.

Mr. Maybury writes on investments.

This article originally appeared in The Free Market, November 1985.