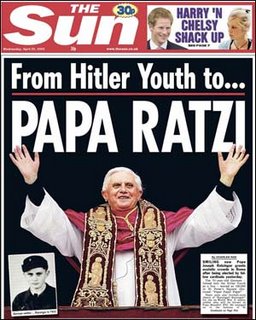

Indioheathen notes: I cut and pasted this from Indian Country Today, being that I think it is informative and well-written. However, the editor/writer suggests that some sort of re-validation of Indigenous Americans ought to be issued by former Hitler Youth goose-stepper Josef "Paparatzi" Ratzinger, a.k.a. Pope Benedict XVI. In this context, I will apply a simple saying of Russell Means as a response: "I don't care what non-Indians think!"

Indioheathen notes: I cut and pasted this from Indian Country Today, being that I think it is informative and well-written. However, the editor/writer suggests that some sort of re-validation of Indigenous Americans ought to be issued by former Hitler Youth goose-stepper Josef "Paparatzi" Ratzinger, a.k.a. Pope Benedict XVI. In this context, I will apply a simple saying of Russell Means as a response: "I don't care what non-Indians think!"The Holy Father and our European problem

Posted: September 29, 2006

by: Editors Report / Indian Country Today

Pope Benedict XVI has joined the ranks of mild-mannered scholars who find themselves in the middle of ferocious controversy for what they thought was an academic remark. Evidently shocked by the reaction to a lecture he gave in September, he met on Sept. 25 with ambassadors from Islamic countries to smooth things over. We sympathize with the Holy Father, but some unexplored aspects of the controversy hold great interest for indigenous people. Perhaps in his willingness to apologize, he might turn his attention to the American Indian.

The invective against the pope keyed on a somewhat tangential passage in a speech he delivered to scientists Sept. 12 during a homecoming to the University of Regensburg. The lecture is steeped in nostalgia for the pope's teaching days in German universities. It is highly interesting, philosophical and even blunt, but very few of the commentators appear to have read it. If they had, we think the pope might be hearing protests, or at least questions, from a much broader range of humanity, including many indigenous followers of ''the Jesus way.'' His remarks on Islam were only part of what could be read, or misconstrued, as a re-emergence of European cultural arrogance.

The passage on Islam, to be sure, was a massively imprudent display of scholarship. (Part of the problem, Vatican sources apparently told The New York Times, was that the pope wrote it himself and didn't consult his in-house Middle East experts. The provisional text posted on the wonderful Web site for the Holy See, www.vatican.va, states: ''The Holy Father intends to supply a subsequent version [...], complete with footnotes.'') Drawing on a 1966 collection of Byzantine documents published in French by the Lebanese Catholic theologian Adel-Theodore Khoury, the pope quoted a religious polemic between the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaeologus (1350 - 1425) and a Persian. The setting itself was highly confrontational; the pope noted it was probably written during the siege of Constantinople by the Turkish Islamic army between 1394 and 1402. Just 50 years later, the forces of Islam completely overran the remains of the Byzantine Empire.

In these circumstances, Manuel II was understandably bitter about Islamic military power.Pope Benedict XVI himself noted his ''startling brusqueness, a brusqueness which leaves us astounded.'' The emperor complained that spreading faith by the sword was ''evil and inhuman.'' This is the passage that is raising the hackles of Islamic radicals, and to tell the truth, it raises our eyebrows. Not that we sympathize with the Islamist street protests. They come across as a cynically manipulated political campaign by a movement intent on perverting the true greatness of the Islamic religion. Some scholars maintain that the current terrorism in the name of Islam really has its roots in European fascism. There is a ludicrous tenor to the threats against the pope now attributed to al-Qaida, along the lines of: ''Apologize for calling us violent and irrational, or we'll blow you up.''

But an indigenous audience has to find great irony in Christian complaints about spreading faith through violence, after the history of the Spanish conquests in America and the more insidious compulsions of the Indian agents in the United States. To be fair, the Dominicans of the 16th century were deeply troubled by the Spanish conquistadors' strong-arm exploitation and conversion of the Native population. Although they were also committed to destroying Native religion, they argued that it should be done by example and peaceful persuasion.

This was precisely the issue of the famous disputation summoned by the Spanish King Charles V at Valladolid in 1550. Was it just to conquer the Indians before preaching the Christian faith to them, since they would be much more amenable to conversion after they were defeated? The Dominican Bartolome de las Casas argued vehemently against using force but he was fighting against the practice of the day, and the outcome of Valladolid was ambiguous at best.

But Pope Benedict XVI raised this whole issue only as an introduction to his main theme, and here is where the truly basic argument begins. The decisive objection against violent conversion, he said at Regensburg, ''is this: not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God's nature.'' He went on to say that Muslim teaching denied that God was limited by rationality. ''Here Khoury quotes a work of the noted French Islamist R. Arnaldez, who points out that Ibn Hazm went so far as to state that God is not bound even by his own word, and that nothing would oblige him to reveal the truth to us.'' This is surely a more profound, if less seized upon, criticism of Islam than the remarks for which the pope is apologizing.

By contrast, the pope affirmed the Greek roots of Christianity. He described his religion as the encounter between the biblical message and Greek rational philosophy. He obviously didn't mean it was simply a historical synthesis. That would be a shocking position for the head of the Catholic Church. He called both traditions the expression of the truth of God's nature. Both describe a rational universe reflected in the rationality of the human soul.

But the pope revived an old problem when he added a geographic slant. His Christianity is not only Hellenistic, it is Eurocentric. ''Given this convergence,'' he said, ''it is not surprising that Christianity, despite its origins and some significant developments in the East, finally took on its historically decisive character in Europe. We can also express this the other way around: this convergence, with the subsequent addition of the Roman heritage, created Europe and remains the foundation of what can rightly be called Europe.''

Some Islamic bloggers are rightly objecting that Hellenistic philosophy had a profound influence on their own religion. Christianity has no monopoly on the thoughts of Plato and Aristotle. In fact, Europe owes a profound debt to Islam for preserving many of its works in Arabic when they were lost in the West. The pope has acknowledged this common ground in some of his other speeches to Muslim audiences. But indigenous Christians might be concerned to learn whether the pope will find common ground with them.

The pope devoted the last half of his lecture to a critique of the modern ''call for a dehellenization of Chrisitanity.'' Taking the long view, he said this program began with the 16th century attack on scholastic theology, the medieval structure based on Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas. Indians actually fared relatively better with the neo-scholastic theologians like Francisco de Vitorio than with modern rationalists like John Locke. At least the scholastics recognized the Native right to property and political sovereignty. So far we can side with the pope.

But we have to ask for clarification when he criticizes what he calls the ''third stage of dehellenization, which is now in progress.'' He attacked a thesis from cultural pluralism: the synthesis with Hellenism ''ought not to be binding on other cultures.'' ''The latter,'' he wrote, ''are said to have the right to return to the simple message of the New Testament prior to that inculturation, in order to inculturate it anew in their own particular milieus. This thesis is not only false; it is coarse and lacking in precision.''

This passage is brief and the vaguest in the lecture, and perhaps the pope would shy away from some of its implications. But in the wrong hands it could be turned into a revival of the European imperial missionary spirit. It seems to deny the validity of non-European religious expression. In its most extreme form, it harks back to the wrong side of the Valladolid debate, the argument of Juan Gines de Sepulveda that Indians did not have a rational soul and were subject by nature to their European masters.

That is not necessarily the position of the pope. We would argue that the Native approach to religion and nature is fully as rational as the European version, and much more respectful.

The long history between Indians and the Catholic Church has many lows, but also some high points in which the papacy has defended Indian rights. Pope John Paul II, a strong influence on his successor, had especially warm relations with the Natives of the Americas. We hope that Pope Benedict would continue this tradition.

He has several current opportunities to repudiate European arrogance. He could acknowledge the campaign for a rescission of the papal bulls justifying the doctrine of discovery. He could repeat the language of Pope Paul III in the 1537 papal bull Sublimis Deus ''that the Indians are truly men.'' He could clarify that the inherent rationality to which he referred under the heading of Hellenism is a property of all humanity, not solely of Europeans.

We have no doubt that this was the true intent of his remarkable Regensburg lecture. But if he is through apologizing to Muslims, perhaps he could now explain himself to the indigenous peoples of the world.

http://indiancountry.com/content.cfm?id=1096413746